becoming a self in history, becoming a self in my street |

||

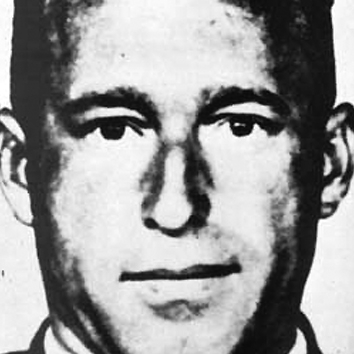

Franz StanglFranz Stangl was a young weaver, who lived in Austria. Wanting to get on, he applied to become a policeman. Although his employer was a kind man, Franz chose not to discuss his wishes with him until he had accepted his new job. When he told him, his employer said that he wished that Franz had come to see him first, because he had intended to offer to finance him for further training. This is the beginning of an incredible story, which begins with something that everyone can recognize. We feel uncomfortable about hurting someone’s feelings and so, despite knowing deep down that we should bring it up, we ignore the feeling and go on regardless, hoping for the best. It is possible that what then went on to happen to Stangl would never have happened if he had listened to that uncomfortable voice that told him his boss actually deserved to be included in his decision. Stangl made decisions like this time and again to avoid trouble and complications. When he became a policeman, the Nazi party was illegal in Austria. He was present when Nazis were arrested and detained. Eventually Hitler marched into Austria and Stangl agreed with other officials to destroy any incriminating papers, so that he would not subjected to Nazi purges of the police force. Because his record was clean, he was seen as good Nazi material. To prepare him to take on unpalatable duties, he was required to sign a form saying he was willing to ignore his religious beliefs if necessary. He took this seemingly insignificant step without discussing it with his wife. Thus he became a candidate for work as a policeman overseeing the Euthanasia project. He had no responsibility for the killing of disabled children and adults. That was done by doctors and nurses. However, he was responsible for returning all the belongings of the disabled victims of these killings to their parents and relatives. Gita Sereny asked him in an interview why he had never questioned the murder of disabled adults and children, he abnegated any responsibility. The decisions were taken by the experts. They knew better than him what it meant to be human in this context. Precisely because he was so malleable in this matter he was then chosen for the next Nazi project. He was invited to meet high-ranking Nazis in Poland and was eventually made the commandant of the death-camp at Treblinka, where Jews were taken to be gassed and then burned to ash. It is estimated that 900,000 people perished there. When the work was completed the camp was dismantled and a farmhouse was built on the site to hide what had happened there. It is now a monument to the dead. After the war, Stangl escaped to Argentina via Rome and lived under his real name for twenty years. He was finally discovered and brought back from Argentina to be tried in Germany for his involvement in war crimes. While in prison serving his sentence he agreed to be interviewed by Sereny. Throughout the interview he refused to acknowledge any responsibility for anything that happened. However, in his last conversation with Sereny he allowed himself for a moment to admit that the life he had had, which he had been prepared to save at any cost, had not been worth the price. The burden of what he carried was so heavy that he acknowledged that death would have been preferable. Sereny experienced that this admission made a deep impression on the state of his soul, and that it had brought him some sense of healing. Nineteen hours after he this conversation, he died of heart failure. Sereny says of that death, ‘I think he died because he had finally, however briefly, faced himself and told the truth; it was a monumental effort to reach that fleeting moment when he became the man he should have been.’

References to works mentioned are on the references page.

| ||

prev |

home • the stories • comment • events • contact | next |